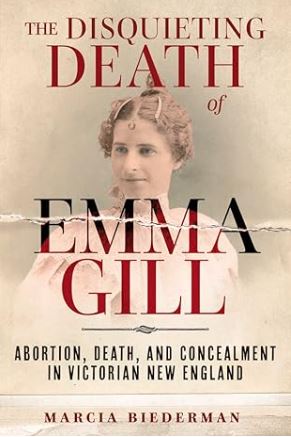

In this episode of Biographers in Conversation, Marcia Biederman shares with Gabriella her approach to writing The Disquieting Death of Emma Gill, Abortion, Death and Concealment in Victorian New England.

Marcia Biederman reveals why she felt compelled to write The Disquieting Death of Emma Gill given the book’s relevance today, more than a century after the events occurred. Marcia explains why she opened the book with a gruesome finding and why she portrayed the abortionist Nancy Guilford as an antihero rather than as a villain, heroine or victim. She also outlines the book’s themes, especially hypocritical attitudes to abortion that continue today in some countries. Marcia shares her narrative strategy, explaining how she crafted a gripping, propulsive narrative that makes The Disquieting Death of Emma Gill read like a true crime novel rather than a biography.

‘The narrative unfolds like a high-stakes crime novel.’

Kirkus Reviews

In 1898, a group of schoolboys in Bridgeport, Connecticut discovered gruesome packages under a bridge holding the dismembered remains of a young woman. Finding that the dead woman had just undergone an abortion, prosecutors raced to establish her identity and fix blame for her death. Suspicion fell on Nancy Guilford, half of a married pair of “doctors” well known to police throughout New England. A fascinated public followed the suspect’s flight from justice, with many rooting for the fugitive. The Disquieting Death of Emma Gill takes a close look not only at the Guilfords, but also at the cultural shifts and societal compacts that allowed their practice to flourish while abortion was both illegal and unregulated.

‘Abortion in the Age of Concealment’

A review by acclaimed biographer and literary critic Carl Rollyson of The Disquieting Death of Emma Gill published in The New York Sun on 28 June 2024.

‘The skilful biographer Marcia Biederman, working in various archives, has assembled a well-wrought narrative, and the result is the creation of a criminal who also became a heroine.’

Carl Rollyson

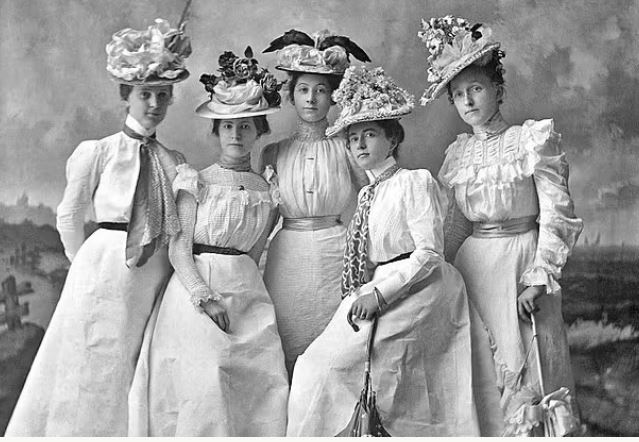

‘Women had a lot to conceal in late 19th century America,’ Rollyson wrote in his review. ‘If a young unmarried woman became pregnant, she risked bringing shame to her family, and also possibly losing that family’s love. Some women had the facts of life concealed from them, so that they knew little about what an abortion entailed. Some newspapers would not even print the word abortion.

Licensed physicians performed abortions when the life of the mother was at stake. Otherwise, unlicensed practitioners performed the illegal operation, very often in rather sordid and unsanitary conditions.

Most abortionists were men, like Nancy Guilford’s husband, Henry, who practiced without a license. Exactly how she came to share her husband’s work is not entirely clear — precisely because this was an age of concealment.

Emma Gill had every reason to suppose that Nancy Guilford, who came highly recommended, would be able to help her. Exactly what went wrong could be determined only by an autopsy because, again, the circumstances of the procedure had to be concealed.

Nancy had already served one prison term when Emma consulted her. Yet Nancy remained a trusted figure in her community of Bridgeport, Connecticut, and when Emma Gill’s body, sawed into several parts, was discovered by a group of boys under a bridge, many people found it hard to believe that Nancy had been responsible.

Could a woman have the skill and strength to dismember a body? That was just one of the questions the press asked. Nancy dressed well, was fond of jewellery, and to look at her she seemed hardly the type to commit such a gruesome crime.

To give away too much of the story would be more than spoiling it. It took law enforcement a long time to figure out who ought to be charged with the crime, and though Nancy Guilford eventually became the suspect, she eluded them for quite some time — much to the amazement and even admiration of newspaper readers who followed the case.

It also took Marcia Biederman an extended period to put together how it was that Emma Gill ended up in pieces. This skilful biographer, working in various archives, has assembled a well-wrought narrative, and the result is the creation of a criminal who also became a heroine.

To understand Nancy Guilford, Ms. Biederman carefully situates her in 19th century New England. Nancy pretended, like her husband, to have a medical degree, but at the same time she remained a devoted mother, with her children making every effort to protect her.

As Ms. Biederman shows, Nancy was a much more admirable person than her husband, who tended to prey on helpless women. Nancy stayed with him through many of their legal ordeals, as well as when both were imprisoned. It would seem that she did so in an effort to keep her family together.

What Ms. Biederman cannot tell us is why, even after serving a prison sentence, Nancy Guilford returned to work as an abortionist. It was a lucrative practice, to be sure, but as her daughter Eudora realized, Nancy was putting at risk the very family she wanted to preserve.

What is unsaid but seems apparent from Ms. Biederman’s careful research is that Nancy Guilford, in spite of the Emma Gill case, was good at her work and believed she was helping women — even if that meant she had to lie about what she did.

There never seems to be a dull moment in this book, not only because Ms. Biederman knows how to sustain the momentum of a good story, but because what she knows about Nancy has to be built up detail by fascinating detail.

It is tempting to draw parallels to the abortion debate today, but Ms. Biederman refrains from doing so, realizing the power of the story she has uncovered speaks for itself. To editorialize on top of powerful narrative would wreck an impeccable biography.

Sometimes readers of biographies have to do the analysis for themselves, and to work out the relevance of a life like Nancy Guilford’s to the current moment. Conclusions are bound to differ, but what cannot be gainsaid is the consequences of a society in which concealment is itself a form of punishment.’

The Disquieting Death of Emma Gill is Marcia Biederman’s fourth nonfiction work about women whose stories should be better known. Her previous books are A Mighty Force, about Pennsylvania coal town physician Elizabeth Hayes; Scan Artist, about speed-reading entrepreneur Evelyn Wood; and Popovers and Candlelight, about New York restaurateur Patricia Murphy. As a journalist she was on the staff of Crain’s New York Business and contributed more than 150 pieces to the New York Times. Her work has appeared in the International Herald Tribune, New York Magazine, the New York Observer, Newsday, and the Christian Science Monitor.

Read what path led Marcia to Emma Gill’s story and why she believes it is important to tell her story today. Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Marcia Biederman:https://www.historyinthemargins.com/2024/03/20/talking-about-womens-history-three-questions-and-an-answer-with-marcia-biederman-2/

Marcia Biederman’s recent op-eds connecting The Disquieting Death of Emma Gill to current events about abortion rights and laws preventing abortion:

• “When Abortion was a Crime in Connecticut,” CT Mirror, Jan. 23, 2024

https://ctmirror.org/2024/01/23/ct-abortion-laws-crime/

• “When Americans Shrugged at Criminal Abortion,” NY Daily News, Jan. 23, 2024

• “Hollywood, the GOP, and the Widespread Support of Abortion Rights,” Hartford

Courant, November 24, 2023 https://bit.ly/3N2ajSG